Chianti Classico

Vintage image sourced on Pinterest

If your impression of Chianti is associated with inexpensive fat-bottomed straw-wrapped “fiasco” bottles, often used as candle-holders once empty, you are in for a treat. This tasting zooms in on Chianti Classico, a region distinct from Chianti, and even better, on its recently approved additional geographic units within the region, the UGAs (Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive).

In some ways, it’s a pretty geeky tasting theme, one that dives into terroir, grape varieties and winemaking methods, requiring a bit of work to find the right wines and allowing you to taste some of the many shades of Chianti Classico and form your own impressions of the region’s wines.

In other ways, it’s one of the simplest tastings of all, since Chianti Classico is the OG Chianti, defining wines from the hilly region between Florence and Siena, iconically represented by the black rooster on every bottle. It’s arguably the most famous Italian wine, the one you were probably introduced to long before you knew anything about wine, especially if you were lucky enough to grow up eating out on special occasions in old-school Italian-American joints with red-checked tablecloths and “sauce” (or even better, “gravy”) on everything like I did.

Stuff to know

Place

Chianti Classico is the historic region for Chianti, the hilly region in Tuscany north of Sangiovese’s other famous haunts: Brunello di Montalcino, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and Morellino di Scansano, and west of Italy’s famous Apennines, the mountain range that cuts a vertical line through Italy.

To clear up any confusion between “Chianti Classico” and “Chianti,” we have to cover a bit of history. Once upon a time, Chianti wines could only be made in the lands between Florence and Siena. The lands of the black rooster, or so the legend goes. Said legend being a story originating in the Middle Ages, during which Florence and Siena’s respective republics were at war. To settle a border dispute, the republics decided to allow two knights to ride toward the opposing city, agreeing that a border would be drawn where they met. The caveat being that the knights could leave at dawn, as signified by a rooster’s crow, no earlier. So of course the scheming began.

Siena chose a white rooster, and treated it well in hopes that it would perform the best. Florence chose a black rooster, and starved it in a cage. The starving rooster crowed long before dawn in its desperation to be fed, so the Florentine knight made it almost all the way down to Siena before meeting his opponent. The majority of the Chiati zone in between became the territory of the black rooster, later a symbol of the Lega del Chianti that subsequently controlled the area.

From medieval times through 1716, when the borders of Chianti were officially defined, all Chianti came from this region between Florence and Siena. It wasn’t until 1932 that the Italian government decided to enlarge the historic zone, allowing “Chianti” to be made in many other parts of northern Tuscany beyond the historical zone. Over time, producers wanting to cash in on a growing trend for cheap Chianti, especially in the 1950s and 60s, when the iconic straw-wrapped “fiasco” bottles reached peak international popularity, began to plant vines in areas that could technically make “Chianti,” even if they probably shouldn’t.

Quality-focused producers all over the region began to fight back in the late 60s and 70s. Super Tuscans using Bordeaux grape varieties were born, Bordeaux-style bottles replaced fiascos for all styles of Chianti and both the Chianti and historic Chianti Classico regions fought for higher quality-focused regulations and classifications.

Chianti officially became its own DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) in 1967, and then finally earned its DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita), the highest quality classification for Italian wines, in 1984. All the while, the historic region of Chianti Classico was still treated as a sub-zone within Chianti.

In 1996, Chianti Classico officially broke up with the broader Chianti region, reclaiming the historic region and receiving solo DOCG status with a stricter set of rules than the Chianti DOCG. This is also when the medieval legend’s black rooster started to be used on all Chianti Classico bottles as the symbol of the Consorzio Vino Chianti Classico.

Chianti Classico is still a big area though, even without broader Chianti, encompassing about 177,500 acres (71,800 hectares), though much of the area is forested or dedicated to olive groves, with only about 16,800 acres (6,800 hectares) planted to grapevines. For comparison, Barolo only has about 3,700 acres (1,500 hectares) under vine, and Brunello di Montalcino has about 5,200 acres (2,100 hectares) under vine.

In Barolo, wines coming from certain communes and vineyards are known for certain characteristics, and the entire DOCG area has been thoroughly mapped, discussed and debated, so that certain areas’ and single vineyard’s wines are well known and prized today. In 2010, the MGAs (Menzione Geografica Aggiuntiva) were added to the Barolo DOCG classification, further clarifying the region’s terroir variations using a similar format to French crus.

In the years since winning their independence from Chianti, Chianti Classico producers began to realize that their historic territory needed further classification, too. Chianti Classico wines’ differences were being discussed in terms of grapes in the blend and winemaking techniques more often than for their terroir-based variations, even from an area bigger than Barolo or Brunello di Montalcino.

In 2023, Chianti Classico finally made it happen, adding 11 UGAs (Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive) to their classification…with some caveats. Finally, this large region with its three primary soil types, vastly variation elevation, forested areas impacting microclimates and traditional variations in viticulture and winemaking agreed to draw up the UGAs to function much like Barolo’s MGAs or Burgundy’s climats, each UGA identified by its own characteristics. Some UGAs correspond closely with existing communes, while others form new areas. The catch is that the UGAs will only begin to appear on Gran Selezione bottles at first, which are the highest quality and longest-aged Chianti Classico wines.

Still, I chose to zoom in on 6 of the 11 UGAs in this tasting in an effort to give you some perspective on the variations between them, allowing you to form your own opinions about each.

Grape(s)

Chianti Classico is synonymous with Sangiovese, the most-planted grape in Italy, whose spiritual home is in Tuscany, where there are endless permutations of the grape, its clones, the conditions and soils in which its grown and the ways wines are made from it.

But. Chianti Classico is also traditionally a blend, even if the blend’s composition has changed a lot over the years.

Before 1872, there was no official blend, or “recipe” for Chianti Classico. Many used the local red grape Canaiolo as the primary grape, blending it with smaller amounts of Sangiovese and local red grapes Mammolo and Marzemino. White Chianti wines were mostly made with Trebbiano and San Colombano, though Malvasia and Vernaccia were sometimes used.

In 1872, Bettino Ricasoli, nicknamed the Iron Baron and the head of a family with centuries of Chianti wine production behind it, began experimenting at Castello di Brolio in Gaiole. He grew and vinified the local grape varieties separately, documenting each one’s characteristics. He worked with a professor at the University of Pisa to adjust winemaking practices, using sealed vats during fermentation instead of open ones, and reducing the grapes’ skin contact from weeks to 5-6 days. He traveled throughout France, learning the viticultural and winemaking techniques used in Bordeaux, Burgundy, Beaujolais and the Languedoc. And he created what became the Chianti “recipe,” a blend with Sangiovese as the primary grape, using Canaiolo in smaller proportions. He also recommended using the white grape Malvasia for lighter Chianti wines. Over time, Ricasoli’s recipe became the go-to Chianti blend, though many producers substituted the easier-to-grow white grape Trebbiano for Malvasia.

In 1967, the Chianti DOC (with Chianti Classico as a sub-zone) made an official blend part of its regulations: Sangiovese at 50-80%, Canaiolo at 10-30%, and white grapes Trebbiano and/or Malvasia at 10-30%, with the ability to use some complementary red grapes like Colorino at a maximum of 5%. Ricasoli’s blend had evolved a bit, but was still in use and now official.

In 1984, Chianti (with Chianti Classico as a sub-zone) won its DOCG, and the blend changed again, this time with Sangiovese increasing to 75-90%, Canaiolo dropping to 5-10%, and Trebbiano and/or Malvasia dropping to 2-5%, with the ability to use other complementary red grapes for up to 10% of the blend.

In 1996, when Chianti Classico became a separate DOCG, the official blend changed again, and Sangiovese was allowed to be up to 100% of the blend. The white grapes Trebbiano and/or Malvasia were now optional up to 6%, and Canaiolo was optional up to 10%. Complementary red grapes could be up to 15% of the blend…and they didn’t have to be local grapes.

International grape varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot and Syrah could be used for up to 15% of the blend, bringing what were once highly local wines closer to Super Tuscan styling, confusing Chianti Classico’s identity and making grape variety a new focal point of differentiation, rather than terroir.

In 2002, the minimum percentage of Sangiovese increased further, moving up to 80%, and the maximum percentage of other red grapes went up from 15% to 20%. White grapes were no longer allowed to be part of the blend after 2005. There have been a few adjustments since 2002, particularly to the Gran Selezione wines’ requirements, which must be a minimum 90% Sangiovese, and can only use local red grapes like Canaiolo, Ciliegiolo, Colorino and others for the remaining 10%, making these the only Chianti Classico wines required to use only local red grapes, even today.

In recent years, producers have increasingly moved away from using international grape varieties, even though they’re still allowed in Chianti Classico and Riserva wines. In my personal experience, even small amounts of the international varieties can dramatically change the color and character of Chianti Classicos, so I can’t help but to be encouraged by moves back toward local heritage and tradition, not to mention terroir. When the grapes are all local (or 100% Sangiovese), the differences between wines that are due to place tend to come into sharper focus.

Winemaking

Much like the changes to the grape variety(ies) comprising Chianti Classico over the years, winemaking practices have seen plenty of shifts, too. Everything from how best to train the vines, when to harvest, whether to destem, how long skin contact should be, what type of vessels to ferment in and at which temperatures to what oak aging should look like is up for debate.

Even with all of this potential variation on the table, it’s the oak aging that garners the most interest. In the 1980s and 90s, newly toasted 225L French oak barrels (barriques) entered the Chianti Classico scene, adding far more overtly oaky flavor to the wines than had been seen before, along with abundant aromas and flavors of vanilla, cinnamon, clove and other baking spices. This corresponded with an increasing use of international grapes, moving Chianti Classico stylistically more toward the Super Tuscans and other big red wines popular at the time.

As the trend for overtly oaky red wines faded, producers moved back toward larger barrels with varying levels of newly toasted oak. These days, producers might use 500L tonneaux, large oval-shaped botti with 10-300hL of capacity, or even the occasional traditional chestnut cask, and they’ll carefully select their oak source: usually France, but sometimes Slavonia in Croatia.

Many producers will include their oak-related choices on their wines’ descriptions, at least online, since the percentages of new oak, which type of barrels are used and how long the wine rests in barrel is still a very hot topic, and can give you some idea of what to expect from the wine.

Styles

In Burgundy, the pyramid depicting the various tiers of wines is a quality- and place-focused one, with regional-level wines at the bottom with the highest amount of production and Grand Cru wines from small, select vineyards at the top. Chianti Classico’s pyramid is more style-focused, since its primary differentiation point is the length of aging, much like the wines in Rioja.

At the bottom of the pyramid are Chianti Classico wines, without any qualifier. These wines must be aged for a minimum of 12 months and must be comprised of at least 80% Sangiovese grapes, with a maximum of 20% of authorized red grapes allowed for the remainder. Chianti Classico wines are the easiest to find, since they comprise about 60% of the region’s total production.

The next level up is for the Chianti Classico Riserva wines. These wines have the same blend requirements as Chianti Classicos, but the aging requirement is longer, with a minimum of 24 months of aging (of which 3 months must be in bottle). Riserva wines make up about 35% of the region’s total production, and are relatively easy to find.

Chianti Classico Gran Selezione wines sit at the top of the pyramid, comprising just 5% of the region’s total production. This category has only existed since 2014, so it’s relatively new. These wines have different blend requirements, with a minimum of 90% for Sangiovese, and a maximum of 10% for the other red grapes…which can only be local red grapes, rather than international ones. Gran Selezione wines must be aged for at least 30 months (of which 3 months must be in bottle), and the grapes must be estate-owned, meaning that producers cannot buy grapes from others’ properties within Chianti Classico for use in these wines.

As of 2023, Gran Selezione wines are allowed to include the UGA they’re from on the label, unless they’re single vineyard wines, in which case the producer can just include the vineyard name instead.

What to look for in this tasting

Chianti Classico wines aren’t as easy to summarize as you might think. They’re all Sangiovese-based, so there’s a common thread in that regard, but the choices producers make around which other red grape varieties to include in the blend, how long to age the wines and in which types of oak, and most important, where the grapes are grown, can dramatically alter the wines.

In general, Chianti Classico wines tend to have high acidity, which can often feel tangy, like what you’d taste eating sour cherries. The tannins in these wines can be moderate or high, and are often sandy, grainy or chalky, making their presence easily known. Flavor-wise, there are pretty much always cherries. Sour cherries, red cherries, black cherries, dusty cherries, which, ok fine, is really just a description I use a lot that isn’t actually a real thing.

Aside from cherries galore, there can be other fruits like blood oranges, red currants and plums, dried and fresh herbs like oregano, thyme, rosemary and mint, and flavors of leather, balsamic vinegar, cloves, tobacco, coffee, mushroom, truffle and tomatoes. Also clay pots and tomato leaves, which again, could just be my own interpretations.

As the wines age, the fruit flavors tend to become more dried than fresh, and the savory flavors of balsamic vinegar, leather, mushroom, coffee, tobacco and truffles tend to become more prominent.

Many Chianti Classicos wines are medium-bodied, with delicate aromas and subtle oak influence, though others are full-bodied with evident new oak aging and even the Cabernets, Merlot or Syrah in the blend, deepening the wines’ color and flavors and adding more black fruit and tannin to the mix.

The wines

Chianti Classico is a hilly region with a wide variety of different aspects, elevations and microclimates affecting each of its vineyards. The introduction of UGAs (Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive) to the classification in 2023 goes some way toward characterizing the wines from certain parts of the region, but it’s not foolproof, since there’s still a lot of terroir variation within a UGA, and producers’ blending and winemaking choices matter, too. Nevertheless, this tasting zooms in on 6 of the 11 UGAs in an effort to focus more on terroir than the grape varieties in the blend or winemaking choices.

The caveat is that the UGAs can only appear on Gran Selezione bottles’ labels at first, the highest quality and longest-aged Chianti Classico wines, and producers don’t have to include them yet, especially for single vineyard wines.

You can select Chianti Classico or Riserva wines for this tasting, not just Gran Selezione wines. To find your wine, it will take a bit of research to determine which UGA your selected Chianti Classico is from, which can be done by searching for the producer’s estate location within Chianti Classico online or by asking your local retailer for help.

#1: Chianti Classico: Castellina

The Castellina UGA is located in the central-western part of Chianti Classico, and Castellina is, on average, the coldest town in the entire Chianti Classico zone, thanks to its elevation and exposure. The vineyards, though, lie on more varied terrain, so while the wines from Castellina can generally be characterized by bright, expressive fruit, high acidity and fine tannins, there are variations worth considering. In one part of the Castellina UGA, woods cover most of the landscape and the vineyards tend to lie on slopes facing inward from higher peaks, sheltered from the coldest winds. In another other part, vineyards lie in a more open landscape at higher altitudes than the wooded areas. The variations in elevation are as high as 985 feet (300m) between the lowest and highest points.

While there are variations in soil composition too, the vineyard elevations within Castellina tend to drive the most significant variations in style, with wines coming from the highest elevations showing more bright red fruit character with savory, delicate tannins, while those from the mid-slopes tend to show darker, riper fruit character and more solid tannins, which only continues to become darker and more solid in wines from the lower slopes, which can also have higher alcohol levels thanks to the riper fruit.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): Stick with a Chianti Classico (any quality level, including single vineyard wines) from the Castellina UGA

#2: Chianti Classico: Castelnuovo Berardenga

Castelnuovo Berardenga is one of the southernmost UGAs, east of the city of Siena and south of the Gaiole UGA. Though vineyard elevation and soil type are variable factors in this southern UGA, generally, the wines from Castelnuovo Berardenga tend to showcase the UGA’s warmer climate. Think dark, ripe fruit and strong, austere tannins, though wines from vineyards with Alberese (calcareous clay) soils will often show brighter acidity than you might expect from these southerly climes.

Some producers in Castelnuovo Berardenga, like San Felice and Fèlsina, have been including “Castelnuovo Berardenga” or “Berardenga” on labels for years, long before the UGA became official, as a way of showcasing the area’s distinct - now officially recognized - character.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): Stick with a Chianti Classico (any quality level, including single vineyard wines) from the Castelnuovo Berardenga UGA

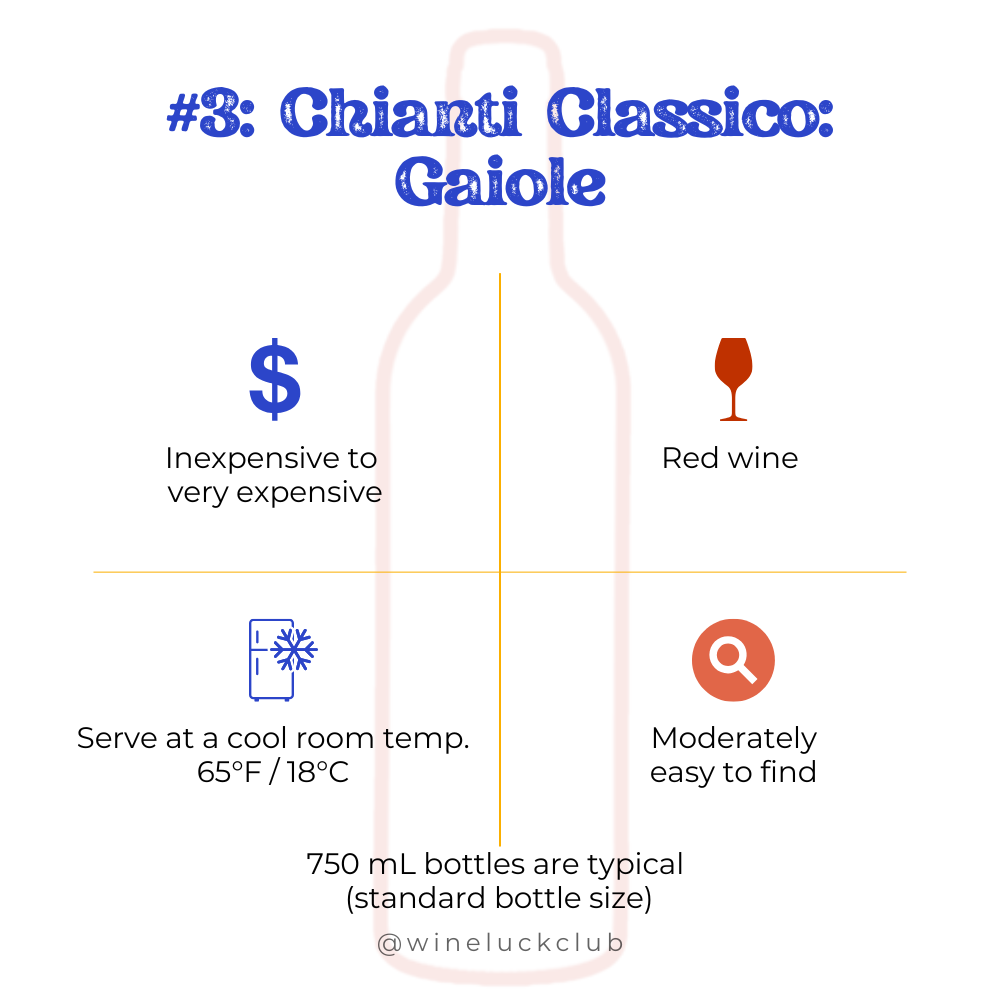

#3: Chianti Classico: Gaiole

The Gaiole UGA lies to the north of Castelnuovo Berardenga, and is unusual in that its namesake communal center sits in a valley, rather than on a hilltop. Gaiole actually lies in a basin at the foot of the Monti del Chianti range, making it one of the coolest spots in all of Chianti Classico. Nevertheless, there are still many variations in vineyards’ elevation and soil composition, even within the UGA. Generally, the wines from Gaiole are known for bright acidity and vibrant tension, elegant, yet fleshy fruit and plenty of tannic structure giving the wines age-worthy backbone.

The famed “Iron Baron” Bettino Ricasoli’s Castello di Brolio is located here, still producing some of the region’s best-known wines, even more than 150 years after his original Chianti “recipe” was created.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): Stick with a Chianti Classico (any quality level, including single vineyard wines) from the Gaiole UGA

#4: Chianti Classico: Greve

The Greve UGA, in the northeastern part of Chianti Classico, is known for its namesake river, the Greve, which winds its way through the Greve valley, creating a distinct microclimate for the many vineyards that line its surrounding slopes. Other parts of the UGA are more varied, especially where the Greve river veers westward and the landscape changes, opening up to gentler hills and more clay-based soils.

The wines from Greve aren’t the easiest to generalize, since the slopes’ varying aspects and elevations contribute to wines that can have quite dark, ripe fruit character and subtle tannins in some areas, while others produce wines with brighter acidity, predominantly red fruit and strong, austere tannins.

What to ask for: Ask by style name

Alternative(s): A Chianti Classico (any quality level, including single vineyard wines) from the Lamole or Montefioralle UGAs

#5: Chianti Classico: Radda

The Radda UGA, located in the central eastern portion of Chianti Classico, doesn’t benefit from having a bunch of prestigious producers within its borders, like the Castelnuovo Berardenga, Gaiole, Panzano and Castellina UGAs. What Radda does have, though, is a cooler climate, thanks to the nearby Monti del Chianti and forestlands keeping things chilly.

For much of its history, Radda’s chilly conditions weren’t a good thing. The Chianti Classicos from here were pale, austere and the kind of tart that borders on underripe. Radda was (and is) usually the last place where fruit ripens in Chianti Classico. Climate change and shifting preferences have allowed Radda to undergo a renaissance in recent years though, since the wines from here are now considered some of the most elegant and vibrant in the region. They’re still usually paler than other Chianti Classicos, but no longer too light a shade. Many of these wines showcase vivacious acidity with red fruit character and plenty of finesse.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): Stick with a Chianti Classico (any quality level, including single vineyard wines) from the Radda UGA

#6: Chianti Classico: Panzano

The Panzano UGA is smack dab in the center of the Chianti Classico region, in the southwestern part of the Greve commune (though it’s still a separate UGA). Panzano is known for its two opposing slopes, one facing east, the other west, as well as its suite of prestigious producers like Fontodi and Monte Bernardi.

The eastern slope is known for having a cooler microclimate, so that the wines from its vineyards tend to have a brighter, lighter color, predominantly red fruit character and firm tannins. On the western slope, the wines tend to have riper, darker fruit character and can sometimes showcase more earthiness and a subtle bitterness that complements austere tannins.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): Stick with a Chianti Classico (any quality level, including single vineyard wines) from the Panzano UGA

Tasting tips

The eats

This tasting is your chance to bust out your favorite tomato-based dish. If it’s still August when you’re reading this, skip the sauces and head straight for the garden, using up all of the last of the season’s goodness to make simple pastas with blistered cherry tomatoes, or skip cooking entirely and just use the fresh tomatoes.

If the weather is chillier when you’re reading this, feel free to dive into all of the richness that can be found in meaty stews or grilled cuts of lamb or beef.

If you want to keep things extra-simple, set up a pizza bar or order in pizzas from your favorite local place.

Charcuterie-wise, aim for classics like Prosciutto Toscano, Mortadella, salami, Pecorino toscano, aged Parmigiano Reggiano and Asiago, marinated artichokes, olives, grapes, dried apricots and the snack-iest Italian breadsticks, Grissini, or the little crispy rings of Taralli, my favorite study snack when I lived in France.

The prep

This tasting is going to take a bit more work for your guests, so I recommend giving them at least three weeks to find their wines, depending on where you live. The reason for the extra work is the terroir-focus this tasting takes, zooming in on the Chianti Classico region’s newly approved UGAs, or sub-regions. The sub-regions were only recently approved, and only for Chanti Classico’s highest quality and longest-aged wines, the Gran Seleziones…and even these wines won’t necessarily have the sub-region clearly marked on the label until the 2027 vintage is released.

However, you and your guests do not have to splash out for Gran Selezione wines for this tasting (unless you want to). You can enjoy Chianti Classico and Riserva-level wines - the catch is that finding the right ones will just take a bit more research. You and your guests can either search online to find wines from a particular sub-region, based on where the estates are located, or ask your local retailers for help.

Price-wise, there’s a wide spending range, especially since prices tend to increase as you go up the quality/length of aging ladder from Chianti Classico to Riserva to Gran Selezione wines. It’s up to you as a host to decide if you want to select a particular quality/length of aging level for this tasting, if you want to set a price range for your guests, or if you want to let your guests decide what they’re each comfortable spending. If guests are finding the wines’ prices to be prohibitive, you can invite them to split their assigned wine’s cost with a friend or partner, widening the tasting group.

A note on the tasting order: The wines are listed in the order of which should be included first. If you have fewer than 6 wines/guests, you’ll still have a well-rounded experience. However, the order in which you taste the wines, regardless of how many wines are included, is recommended as follows:

Chianti Classico Radda

Chianti Classico Castellina

Chianti Classico Gaiole

Chianti Classico Greve

Chianti Classico Panzano

Chianti Classico Castelnuovo Berardenga

Sources

Consorzio Vino Chianti Classico

Chianti Classico: The Atlas | Alessandro Masnaghetti

Chianti Classico: The Search for Tuscany’s Noblest Wine | Bill Nesto, MW & Frances Di Savino