Workhorse Grapes

Vintage image sourced on Pinterest

There are certain wine grapes that are considered “lesser.” They’re considered workhorses of the wine world because they’re reliable, adaptable, easy-to-grow, long-lasting and versatile. They’re grapes that show up year after year, usually as supporting cast, blended with other, more prestigious grapes.

There’s no real caché in making “great” wine from these grapes, even though more and more winemakers are re-discovering old workhorse vines that, when treated well, make excellent, or at least thoroughly enjoyable, wine. There are also new winemakers who can only afford to buy these “lesser” grapes, using them as an opportunity to showcase what they - and the grapes - can really do.

And what’s wrong with a good, affordable workhorse, well made? I am, after all, a sucker for “peasant foods,” all the ugly-delicious dishes made from cheap cuts of meat or plants that grow easily, even in challenging years. Who doesn’t love a bœuf Bourguignon, a feijoada, a ribollita, a ratatouille or a properly slow-smoked barbecue? If peasant food has earned its place in top restaurants, workhorse wines deserve their moment in the sun too.

Stuff to know

Most wine-producing countries have a workhorse grape. Or three.

Even the most recent of the world’s wine regions, like those in Denmark and Sweden, already have go-to reliable grapes like Solaris, capable of withstanding chilly weather and short growing seasons while showcasing versatility through white, sparkling and orange wines.

France has several workhorse grapes, from Carignan and Cinsault to Grenache and Alicante Bouschet, and most overlap with Spain, where the names might change, but the grapes still work just as hard on the other side of the Pyrenees.

In Germany, there’s Müller-Thurgau, and in Italy, there are so many that it’s probably best to just read Ian d’Agata’s Native Wine Grapes of Italy if you want a run-down that goes way beyond the country’s near-ubiquitous use of Trebbiano and its relations.

Australia, South Africa and California are now known for having some of the world’s oldest vines, a circumstance that might surprise the wine world’s Europhiles, and many of them are workhorse grape varieties like Grenache, Cinsault, Chenin Blanc, Carignan and Zinfandel, once planted to be used in fortified wines, distillation or as cheap daily-use-style table wines, now rediscovered for their versatility and quality potential.

Even grapes like Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc can be considered workhorse grapes in some parts of the world, especially since both varieties produce consistently high yields.

So what makes a particular grape variety a workhorse, so to speak? These are grapevines that are reliable, easy to grow, versatile, good for blending or solo use and hardy, even (or especially) in difficult vintages. They were once revered for these qualities, but used to make quantity-focused, rather than quality-focused wines.

Everything comes back around in the end though, and these grapes are no exception. Especially as the criteria for “great” wine has expanded in recent years, while wine quality across the board has risen exponentially since the 80s and 90s.

It doesn’t hurt that the workhorse vines themselves are often old, resilient and consistent. If they’ve successfully avoided disease as time passed, they’ve generally become increasingly weather-tolerant as their roots burrow deeper and deeper into the soil and bedrock below. They’ll produce fewer and fewer grapes per vine, but the grapes themselves tend to become more concentrated, with more flavor to offer. And when that happens, workhorse grapes that were once largely ignored become interesting again.

What to look for in this tasting

The commonality here is in the theme: all of these wines are made from workhorse grapes. Beyond that, there is a huge range of aromas, flavors, acidity, tannin and body levels in these wines. Some are white, some are red and sometimes, producers use these grapes to make wines whose shades fall somewhere in between. In this case, it’s best to get into the wine descriptions themselves to get a better idea of what you’re in for with each wine.

The wines

#1: Aligoté

When I lived in Burgundy, France pre-Covid, Aligoté (“ah-lee-goh-tay”) was just beginning its recent rise in reputation. For most of its lengthy existence in the region, Aligoté has been treated like a second-class citizen, relegated to being used in cocktails like the famous Kir, a blend of crème de cassis (a blackcurrant liqueur) and Aligoté wine. I even had classmates who proclaimed that was all Aligoté was good for: being used as a blending wine in cocktails.

Luckily, there are producers who have recognized Aligoté’s potential, particularly when planted in better sites, the ones that have always been reserved for the region’s famed Chardonnay grapes. Bouzeron in particular has become a hotbed for quality Aligoté. Some top Burgundy producers have begun adding Aligoté wines to their offerings, further increasing the wines’ reputation.

Aligotés tend to have racy acidity and a lean body, qualities that once bordered on the wrong side of under-ripe, therefore making the wines good candidates for blending with sweet blackcurrant liqueur, softening those harsh edges. These days though, winemakers know how to coax ripeness out of the grapes, resulting in wines that still have racy acidity and light bodies, but in an enjoyably refreshing way, rather than face-puckeringly tart. Aligoté wines tend to have flavors of green apple, white peach, lemon and acacia flowers, sometimes with a minerality that tastes like saline or wet stones. A few producers age their wines in oak barrels, adding some roundness and body, but it’s not common.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): Stick with an Aligoté, preferably from Bouzeron

#2: Chenin Blanc

Chenin Blanc is one of those rare grapes that straddles the line between being “noble” and a workhorse. It’s incredibly versatile, used to make traditional method sparkling wines, semi-sweet wines, botrytized sweet wines, unoaked and oaked dry wines. And there are plenty of Chenin Blanc wines with aging potential to spare, all of which makes the grape a “noble” one. In the Loire Valley in Central France, Chenin Blanc is revered.

However, Chenin Blanc is also a highly productive grapevine. It’s reliable, high-yielding and vigorous in a wide range of soil types, and the high, almost screaming acidity that is a hallmark of its character remains consistent, even when the vines are grown in toasty climes. In South Africa, where Chenin Blanc goes by the name “Steen,” the grape is a workhorse, long appreciated for its ability to retain acidity even in warm inland regions, where the resulting wine was often used to make brandy or sold to huge cooperatives to be blended into wines whose purpose was to be good, cheap wine, rather than memorably delicious wine.

While the grape has been planted in South Africa since the 1600s, it wasn’t entirely clear that it was the same variety as the Loire Valley’s Chenin Blanc until the 1960s. More than half of the Chenin Blanc grown today is in South Africa, where it is the most-planted white grape variety.

Like all of the workhorse grapes in this tasting, Chenin Blanc (or Steen) in South Africa has experienced a revival as new winemakers rediscover the quality potential in the country’s old Chenin vines. South Africa’s Old Vine Project, a nonprofit organization certifying planting dates for vineyards 35 years older, has confirmed that Chenin makes up the largest percentage of South Africa’s old vines. There’s even a Chenin Blanc Association for the winemakers who have brought this beloved old workhorse grape into the spotlight. These days, it’s more of a question of what style of South African Chenin you prefer: oaked or unoaked.

My first-ever experience with an oaked South African Chenin Blanc left me, well…dubious, to say the least. I didn’t understand the appeal, since in that particular wine, it felt like the oak flavors were completely separate from the rest of the wine. A year or so later, I tried one of Adi Badenhorst’s single vineyard Chenins, and I was completely blown away. Since then, I haven’t had an oaked South African Chenin that I haven’t loved. These wines may have flavors of baked pineapple, stewed apples and quince, honeycomb, dried grass, freshly-churned butter, marzipan and vanilla.

If you’re still not sure about oaked Chenin tasting great, try an unoaked one first. If you can’t tell by the label whether the wine spent time in an oak barrel or not, look for words like “fresh” or “fruity,” since some South African producers have added a style indicator to their wines, with “fresh,” “fruity” and “rich” as the key words, and the “rich” wines will generally have either oak influence, botrytization or both. Unoaked South African Chenins may have flavors of lemon, golden apples, pears, white peaches, just-ripe pineapples and mangos, chamomile, orange blossom and honeysuckle.

What to ask for: A dry South African Chenin Blanc

Alternative(s): A Chenin Blanc-based white blend from South Africa or a dry Chenin Blanc wine from the United States, Argentina, Australia or France

#3: Cinsault

Cinsault (”san-sew”), which is also spelled Cinsaut, sans “l,” shares Carignan’s affinity for warm, Mediterranean regions, and its ability to reliably produce plenty of grapes every year, though structurally, they couldn’t be further apart. Where Carignan is high in everything: tannins, acidity, body and color, Cinsault wines tend to be pale, soft, light-bodied reds with fruity, herbal-y flavors.

Unsurprisingly, its delicate structure makes Cinsault an ideal grape for blending into the rosé wines of Provence and the Languedoc, though it also makes a frequent appearance in red blends in the Languedoc-Roussillon and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Old Cinsault vines are found in several countries beyond France’s borders, including South Africa, Chile, Lebanon, Australia and the United States.

While Cinsault is still mostly used in rosé and red blends, the grape has experienced a revival partly thanks to its ability to thrive in hot, dry weather that has increasingly hit southern France and other wine regions like South Africa, Australia, Lebanon and California. Winemakers are also rediscovering the potential in old Cinsault bush vines that have adapted to their respective terroir and often begun to produce fewer and more concentrated grapes over the years.

It also doesn’t hurt that light-bodied, fruity red wines have become more popular in recent years as the never-ending trends that cycle through the wine industry continue their rotation. Wines made entirely from Cinsault tend to be pale and light-bodied with soft, subtle tannins. Their aromas and flavors are less delicate, with plenty of cherry, strawberry, raspberry and red plum sometimes accompanied by violets, dried tobacco leaves, black tea or smoky tar.

What to ask for: Ask by name, preferably a 100% Cinsault wine from France, South Africa, Australia, Chile, Lebanon or the United States

Alternative(s): A Cinsault-based rosé wine, preferably predominantly Cinsault

#4: Carignan

Carignan (kah-ree-nyan”), like Grenache, is a Mediterranean grape claimed by both France and Spain. In Spain, it goes by Cariñena and Mazuelo, depending on the region, and in Sardinia, it goes by Bovale Grande. Further abroad, it sometimes goes by Carignane in the United States.

Carignan, like Mourvèdre, can handle the heat, a particularly valuable characteristic in Southern France’s Languedoc-Roussillon, Northern Spain and Sardinia. For many years, Carignan was grown in sunny, warm Algeria, from which it was brought into France to be blended into French wines.

Even better for producers focused on quantity, Carignan is a vigorous and high-yielding vine, producing plenty of grapes each year. The catch is that when encouraged to do so, said grapes tend not to have the most concentrated flavors, resulting in forgettable wines.

Luckily, as with other workhorse grapes, there’s been a revival particularly focused on old, mostly forgotten Carignan vines, usually bush vines, trained to grow individually up from the soil, with branches sticking up like witch’s fingers, rather than along trellises.

It takes some skill to coax memorably good, if not sometimes great, wine out of Carignan grapes. Carignan wines tend toward high tannins and acidity, with a deep color and powerful astringency that can veer toward bitterness if not carefully handled. Some producers use carbonic maceration, common in Beaujolais, to soften things up. Others simply choose gentleness in their fermentations and macerations in their efforts to avoid uncomfortably tongue-scraping tannic outcomes.

Though wines made entirely from Carignan grapes are increasingly available, the grape is still frequently used as a blending partner. If you can find one, a 100% Carignan wine is ideal for this tasting, so that you can experience what the grape is like solo, rather than as a part of the band. Expect to find flavors of red and black fruits like raspberries, cranberries and blackberries alongside white pepper, licorice, baking spices and fresh herbs like lavender, thyme and rosemary, with the occasional meaty note making an appearance.

What to ask for: Ask by name

Alternative(s): A Carignan-based wine, preferably 100% Carignan, from France, Spain, Sardinia, the United States, Chile, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia or Israel

#5: Grenache

Grenache is claimed by both Spain and France, so who grew it first is under some debate. Sardinia, too, has its own claim to what they call Cannonau. Europe’s history of border shifting has something to do with this murky provenance, since the kingdom of Aragón (the medieval one, not the modern-day region) used to reign over chunks of land on both sides of the Pyrenees, along with portions of Italy and the Mediterranean islands: Mallorca, Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. Who brought the grape from which part of the kingdom to the other first isn’t the easiest to determine hundreds of years later.

Wherever it started, Grenache is essentially a Mediterranean grape, since it thrives in dry, warm, windy climates. It’s a pretty durable vine, which made it a go-to grape for growers around the Mediterranean and during the early years of viticultural exploration in far-off countries with similar climates, like California in the United States, Australia and South Africa.

Grenache often isn’t riding solo, but is instead blended with other grapes, so it can be a bit challenging to pick out exactly what it brings to the party. Generally, wines made entirely from Grenache are on the pale side color-wise, making it easy to confuse them for delicate, thin wines when they’re anything but.

Grenache needs a lot of warmth and sunshine to ripen, and when it finally does, there’s a lot of sugar in the grapes. Sugar turns into alcohol thanks to fermentation, so wines with Grenache in the mix might look pale, but they’re what wine people like to call “big” or “hot” alcohol-wise. Keep an eye on the ABV, since it can be high.

Tannin-wise, Grenache is more chill, with light or moderate tannins that can feel soft and diffuse. It doesn’t bring a lot of acidity to the table, though what it does bring can be plenty in the right winemaker’s hands. Flavor-wise, watch out for ripe red fruits like strawberries, cherries and red plums. I often taste blood oranges and strawberry fruit leather in Grenache-based wines. If you didn’t grow up eating fruit leather (or its more artificial counterpart, Fruit Roll-Ups), plain old dried strawberries are similar enough to make the point. Spices, actual leather and herbal flavors can also make an appearance thanks to Grenache in these wines.

What to ask for: A Grenache-based wine, preferably 100% Grenache, from any country or region, such as the Southern Rhône or Languedoc-Roussillon in France, Rioja, Priorat, Sardinia, Australia, the USA or South Africa

Alternative(s): Stick with a Grenache-based wine, preferably 100% Grenache

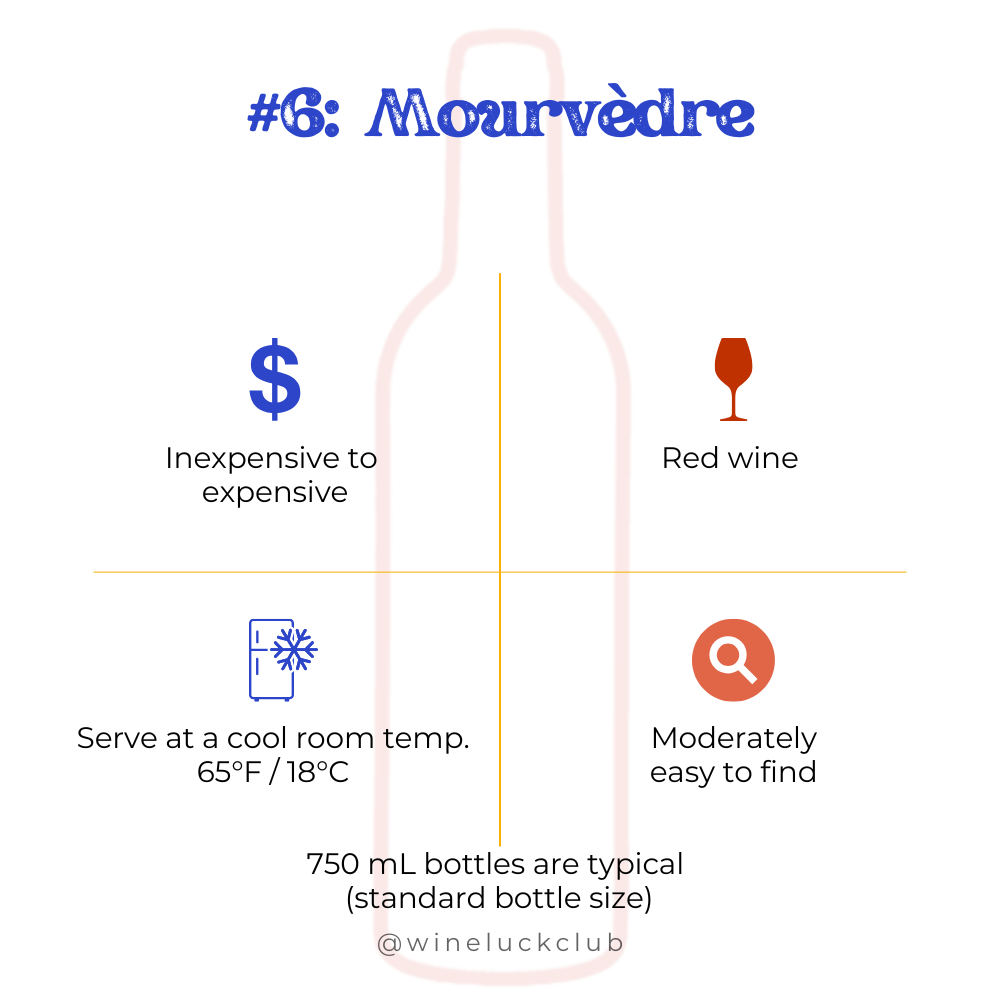

#6: Mourvèdre

Mourvèdre (”moor-veh-druh”) is best known as the “M” in “GSM,” the Grenache-Syrah-Mourvèdre blend that comprises most Southern Rhône reds and their look-alikes in other countries. But Mourvèdre, which also goes by Monastrell in Spain and Mataro in Australia, stands alone on occasion, too.

When I lived in Austin, I was once invited to a tasting to which someone brought a 32-year-old bottle of Domaine Tempier’s Bandol Cuvée Spéciale La Tourtine, a wine that is the essence of Mourvèdre and Provence. If you’ve ever read Kermit Lynch’s Adventures on the Wine Route, you’ll remember this passage: “Domaine Tempier today makes the finest red wine of Provence, but it was not always that way. Up until 1941, the appellation Bandol did not even exist. In the story of the birth of the appellation, and of Lucien Peyraud’s struggle to develop Domaine Tempier into a fine wine, there is all the education one needs into the mysteries of what is involved in creating a fine wine.”

I knew the story of Domaine Tempier going into the tasting, but I’d never before tasted one of their wines with that kind of age. What struck me most was how elegantly humble and honest the wine was. Tasted alongside much more prestigious collector-level wines, the Bandol was like the a great chef’s rendition of a peasant dish. Everything was pure, but simple. Hand-crafted with love. The hardest type of taste to accomplish.

Aside from Domaine Tempier and its role in the creation of Bandol, an appellation where Mourvèdre must comprise at least 50 percent of the wine, there are other regions where Mourvèdre predominates, particularly where Mediterranean climates reign. In Spain’s Jumilla and Yecla regions, wines are made from Monastrell, Mourvèdre’s Spanish moniker, that are intensely dry and savory, though ripe, dark fruit still persists.

Mourvèdres tend to have moderate acidity and thick, coarse tannins that scrape your gums and emphasize the wines’ earthy dryness. These wines taste savory, even though there is plenty of dark fruit, since they are so dry and earthy, often with flavors of Provençal herbs and olives.

What to ask for: A Bandol from Provence or a Monastrell wine from Jumilla or Yecla

Alternative(s): Mourvèdre-dominant wines from Provence or the Southern Rhône, or Mataro from South Australia

Tasting tips

The eats

It feels right to me to serve cheap, good food for this tasting. If you have a smoker, this is the opportunity to slow smoke a pulled pork or a brisket. If you don’t, a feijoada dinner with Brazilian friends comes to mind, with that comfortingly meaty, brothy scent floating down the hall before we even opened their apartment’s door. Add all the accoutrements, from white rice to oranges and collard greens to farofa, if you can get cassava where you live.

If you’re more comfortable making a jambalaya, ribolitta or ratatouille, lean into your strengths and serve your hearty dish with confidence. The goal here is soul-warming food.

If you take the charcuterie route, look for cheeses like Manchego, Mimolette and goat cheeses to pair with Serrano or other cured hams, terrines, crusty bread, green olives, spiced almonds, toasted hazelnuts, cherries and blackberries.

The prep

Though workhorse grapes are common in many wine regions, they’re often blended with other grapes, serving as component parts in wines like Châteauneuf-du-Pape. More and more winemakers are exploring the potential of these grapes solo, but the availability of their wines will vary depending on where you live. To make sure everyone can find their respective wines, it’s worth giving your guests at least 2 weeks’ notice before this tasting.

Price-wise, wines made from workhorse grapes are usually approachably priced and affordable. It’s up to you as a host if you want to set a spending range, or let your guests decide what works for them.

For the white wines, encourage your guests to give their wines some pre-tasting fridge time, since it’s best if the wines are chilled…but not too chilled. Lightly chilled is generally the goal here, so if the wines didn’t get their fridge time before arrival, just keep the ice bucket dunk time brief, since you’ll want to enjoy the texture, not just the flavors, of these wines and that’s difficult to do when they’re ice cold.

As to the reds, the Cinsault will be best with a bit of a chill, aiming for a bottle that’s just cool to the touch. The Grenache, Carignan and Mourvèdre can be served a bit warmer, though “room temperature” for these is really the equivalent of room temperature in French cellars…which is quite a bit chillier than the average home temps are today. Think 65° / 18° - essentially cool enough to warrant snuggling under a blanket during couch time.

A note on the tasting order: The wines are listed in the order of which should be included first. If you have fewer than 6 wines/guests, you’ll still have a well-rounded experience. However, the order in which you taste the wines, regardless of how many wines are included, is recommended as follows:

Aligoté

Chenin Blanc

Cinsault

Grenache

Carignan

Mourvèdre